Abstract

Background and objectives

Economic analyses of drug therapies are highly dependent on the clinical indications for treatment. The cost effectiveness of ramipril has been evaluated in numerous studies, usually based on the results of one specific clinical trial. We estimated the cost effectiveness of this drug across a range of currently accepted therapeutic indications, using a single health economic model and adjusted for quality of life, to compare the different outcomes observed in four clinical trials.

Methods

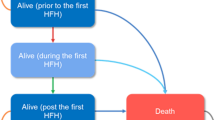

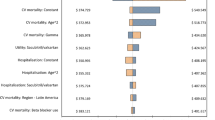

The cardiovascular life expectancy model, a validated Markov model, was calibrated to accurately forecast the results of four trials including AIRE, HOPE, Micro-HOPE, and REIN. We then extrapolated these results over the remaining life expectancy of the patients enrolled in each study and adjusted for the quality of life associated with the observed outcomes. The cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) was then calculated from the perspective of the Canadian healthcare system incorporating the estimated direct healthcare costs associated with treatments and outcomes.

Results

After discounting all costs and outcomes 3% annually, the benefits associated with ramipril ranged from 0.74 QALYs in the AIRE study to 1.22 QALYs in Micro-HOPE. Treatment was estimated to be costsaving for some patient groups, such as those in REIN. The highest cost-effectiveness ratio was observed among individuals enrolled in HOPE ($Can20 000 per QALY in 2002).

Conclusion

Treatment with ramipril appears to be economically attractive across a wide range of patient groups, including those with increased coronary risk and/or diabetes mellitus (HOPE and Micro-HOPE), those with congestive heart failure (AIRE), and those with non-diabetic nephropathy (REIN).

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Lamy A, Yusuf S, Pogue J, et al., on behalf of the HOPE Investigators. Cost implications of the use of ramipril in high-risk patients based on the Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation (HOPE) Study. Circulation 2003; 107: 960–5.

Carroll CA, Coen MM, Rymer MM. Assessment of the effect of ramipril therapy on direct health care costs for first and recurrent strokes in high-risk cardiovascular patients using data from the Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation (HOPE) Study. Clin Ther 2003; 25: 1248–61.

Carroll CA, Coen MM, Piepho RW. Economic impact of ramipril on hospitalization of high-risk cardiovascular patients. Ann Pharmacother 2003; 37: 327–31.

Malik IS, Bhatia VK, Kooner JS. Cost effectiveness of ramipril treatment for cardiovascular risk reduction. Heart 2001; 85: 539–43.

Beard SM, Gaffney L, Backhouse ME. An economic evaluation of ramipril in the treatment of patients at high risk for cardiovascular events due to diabetes mellitus. J Med Econ 2001; 4: 199–205.

Bjorholt I, Andersson FL, Kahan T, et al. The cost-effectiveness of ramipril in the treatment of patients at high risk of cardiovascular events: a Swedish sub-study to the HOPE study. J Intern Med 2002; 251: 508–17.

Erhardt L, Ball S, Andersson F, et al. Cost effectiveness in the treatment of heart failure with ramipril: a Swedish substudy of the AIRE study. Pharmacoeconomics 1997; 2: 256–66.

Hart WM, Rubio-Terres C, Pajuelo F, et al. Cost-effectiveness of the treatment of heart failure with ramipril: a Spanish analysis of the AIRE study. Eur J Heart Fail 2002; 4: 553–8.

Schadlich PK, Huppertz E, Brecht JG. Cost-effectiveness analysis of ramipril in heart failure after myocardial infarction: economic evaluation of the acute infarction ramipril efficacy (AIRE) study for Germany from the perspective of statutory health insurance. Pharmacoeconomics 1998; 14: 653–69.

Schadlich PK, Brecht JG, Rangoonwala B, et al. Cost effectiveness of ramipril in patients at high risk for cardiovascular events. Pharmacoeconomics 2004; 22: 955–73.

Ruggenenti P, Pagano E, Tammuzzo L, et al. Ramipril prolongs life and is cost effective in chronic proteinuric nephropathies. Kidney Internat 2004; 59: 286–94.

Schadlich PK, Brecht JG, Brunetti M, et al. Cost effectiveness of ramipril in patients with non-diabetic nephropathy and hypertension. Pharmacoeconomics 2001; 19: 497–512.

Munter P, He J, Hamm L, et al. Renal insufficiency and subsequent death resulting from cardiovascular disease in the United States. J Am Soc Nephrol 2002; 13: 745–53.

The Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study Investigators. Effects of an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor, ramipril, on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med 2000; 342: 145–53.

Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation. Effects of ramipril on cardiovascular and microvascular outcomes in people with diabetes mellitus: results of the HOPE study and MICRO-HOPE substudy. Lancet 2000; 355: 253–9.

Acute Infarction Ramipril Efficacy (AIRE) Study Investigators. Effects of ramipril on mortality and morbidity of survivors of acute myocardial infarction with clinical evidence of heart failure. Lancet 1993; 342: 821–8.

GISEN Group (Gruppo Italiano di Studi Epidemiologici in Nefrologia). Randomised placebo-controlled trial of effect of ramipril on decline in glomerular filtration rate and risk of terminal renal failure in proteinuric, non-diabetic nephropathy. Lancet 1997; 349: 1857–63.

Grover SA, Paquet S, Levinton C, et al. Estimating the benefits of modifying risk factors of cardiovascular disease: a comparison of primary vs secondary prevention. Arch Intern Med 1998; 158: 655–62.

Grover SA, Coupal L, Paquet S, et al. Cost-effectiveness of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase inhibitors in the secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease: forecasting the incremental benefits of preventing coronary and cerebrovascular events. Arch Intern Med 1999; 159: 593–600.

Heiss G, Tamir I, Davis CE, et al. Lipoprotein-cholesterol distributions in selected North American populations: the Lipid Research Clinics Program Prevalence Study. Circulation 1980; 61: 302–15.

Grover SA, Coupal L, Zowall H, et al. Cost-effectiveness of treating hyperlipidemia in the presence of diabetes: who should be treated? Circulation 2000; 102: 722–7.

Grover SA, Coupal L, Gilmore N, et al. Impact of dyslipidemia associated with highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) on cardiovascular risk and life expectancy. Am J Cardiol 2005; 95: 586–91.

Grover SA, Coupal L, Kaouache M, et al. Preventing cardiovascular disease among Canadians: what are the potential benefits of treating hypertension or dyslipidemia. Can J Cardiol 2007; 23: 467–73.

Grover SA, Coupal L, Zowall H, et al. How cost-effective is the treatment of dyslipidemia in patients with diabetes but without cardiovascular disease? Diabetes Care 2001; 24: 45–50.

Grover SA, Coupal L, Lowensteyn I. Determining the cost-effectiveness of preventing cardiovascular disease: are estimates calculated over the duration of a clinical trial adequate? Can J Cardiol. In press.

Canadian Organ Replacement Register (CORR) Canadian Institute for Health Information. Characteristics of incident ESRD patients, Canada, 2000 [online]. Available from URL: http://secure.cihi.ca/cihiweb/en/reports_corrinsites_sep2002_national_t1_e.html [Accessed 2007 May 1].

Fryback DG, Dasbach EJ, Klein R, et al. The Beaver Dam health outcomes study: initial catalog of health-state quality factors. Med Decis Making 1993; 13: 89–102.

Churchill DN, Torrance GW, Taylor DW. Measurement of quality of life in end-stage renal disease: the time trade-off approach. Clin Invest Med 1987; 10: 14–20.

Resource intensity weights: summary of methodology, 1996/97. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Institute for Health Information, 1996.

Régie de l’assurance maladie du Québec. Manuel des Médecins Spécialistes RAMQ. Quebec City (QC): Régie de l’assurance maladie du Québec, 1996.

Ontario Ministry of Health. Schedule of benefits: physician services, 1992. Toronto (ON): Ontario Ministry of Health, 1992.

Statistics Canada. CANSIM Matrix 9440, Series L. Ottawa (QC): Statistics Canada, 2000.

Statistics Canada. CANSIM Matrix P100200. Ottawa (QC): Statistics Canada, 2000.

Statistics Canada. CANSIM Matrix L95705. Ottawa (QC): Statistics Canada, 2000.

Goeree R, Manalich J, Grootendorst P, et al. Cost analysis of dialysis treatments for end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Clin Invest Med 1995; 18: 455–64.

Laupacis A, Keown P, Pus N, et al. A study of the quality of life and cost-utility of renal transplantation. Kidney Internat 2006; 501: 235–42.

IMS Canada. Canadian Compuscript, November 2000. Point-Claire (QC): IMS Canada, 2000.

Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, et al. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med 2004; 351: 1296–305.

Acknowledgments

Dr Grover, Mr Coupal, and Dr Lowensteyn have received research grants from Pfizer, Aventis, and AstaZeneca. Dr Grover has also been a consultant or participant on advisory boards for Sanofi-Aventis, Merck, AstraZeneca, and Pfizer. This study was investigator-initiated and funded by AstraZeneca Canada Inc., located in Mississauga, Ontario, Canada. All analyses were performed by the study investigators and the manuscript was prepared solely by the authors. The sponsor was permitted to review the manuscript, but the final decision about content was retained exclusively by the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Grover, S.A., Coupal, L. & Lowensteyn, I. Estimating the Cost Effectiveness of Ramipril used for Specific Clinical Indications. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs 7, 441–448 (2007). https://doi.org/10.2165/00129784-200707060-00007

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00129784-200707060-00007