Abstract

We investigated the risk of gastric cancer by subsite in relation to cigarette smoking and alcohol in a large population-based cohort of 669 570 Korean men in an insurance plan followed for an average 6.5 years, yielding 3452 new cases of gastric cancer, of which 127 were cardia and upper-third gastric cancer, 2409 were distal gastric cancer and 1007 were unclassified. A moderate association was found between smoking, cardia and upper-third (adjusted relative risk (aRR) 2.2; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.4–3.5) and distal cancers (aRR=1.4; 95% CI=1.3–1.6). We also found a positive association between alcohol consumption and distal (aRR=1.3; 95% CI=1.2–1.5) and total (aRR=1.2; 95% CI=1.1–1.4) gastric cancer. Combined exposure to high levels of tobacco and alcohol increased the risk estimates further; cardia and upper-third gastric cancers were more strongly related to smoking status than distal gastric cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Until recently, gastric cancer was the second most common cancer worldwide; now, however, with an estimated 934 000 new cases (8.6% of new cancer cases) in 2002 alone, it is in fourth place behind lung, breast and colon and rectum cancers (Parkin et al, 2005). Although declining in Korea, gastric cancer is still the commonest cancer (Shin et al, 2005b).

An extensive review indicates that smoking is a moderate risk factor for gastric cancer (International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2004), but little support exists for an association with alcohol (Gammon et al, 1997; Sjödahl et al, 2006). The possibility of a differential effect of smoking and alcohol consumption on different gastric subsites, however, remains to be clarified.

In a prospective cohort study, we investigated the effects of smoking and alcohol consumption on the risk of gastric cancer by subsite in the National Health Insurance Corporation Study (NHICS).

Materials and methods

The NHICS is a cohort investigation that was designed to assess the risk factors for the incidence of and mortality from cancer (Yun et al, 2005; Park et al, 2006). In brief, the cohort consisted of government employees, teachers and their dependents who were insured by the Korea National Health Insurance (NHI) Program in 1996, had at least one medical examination, and completed a self-administered questionnaire.

The study participants were derived from 692 108 men aged 30 years or over who participated in the National Health Examination Program in 1996 and were in the NHICS cohort. Of the 692 108 participants, we excluded 2732 patients who had cancer at enrollment according to the Korea Central Cancer Registry (KCCR). We also excluded the following because of missing information: 214 for weight or height, 9936 for smoking, 3019 for alcohol intake and 6573 for dietary preference. Ultimately, 669 634 participants were included.

Based on questionnaire responses at the baseline examination of the NHICS cohort, the participants were classified as ‘current smokers’ if they reported smoking currently for at least 1 year, ‘nonsmokers’ if they never smoked and ‘former smokers’ if they had smoked but quit. Current smokers were further classified by the average number of cigarettes smoked per day (1–19, ⩾20) and duration of smoking (1–19, 20–29, or ⩾30 years). Alcohol intake per day was categorised as follows: no drinking (0 g), light drinking (1–14.9 g), moderate drinking (15.0–24.9 g) and heavy drinking (⩾25.0 g). Total daily alcohol intake was expressed as the number of glasses per week of Korea's most popular alcoholic beverage, ‘Soju’. One glass of Soju contains about 12 g of ethanol. A preference for saltiness in food (low salt, normal and salty) was included because of possible relevance to stomach cancer (Tsugane et al, 2004). We used the World Health Organisation body mass index (BMI) standards for Asians (World Health Organisation, 2000).

The principal outcome variable was incident gastric cancer cases identified from the KCCR, a nationwide hospital-based system that includes 94% of the country’s university hospitals and 96% of the resident training hospitals; it covers at least 90% of the newly diagnosed malignancies in Korea (Ministry of Health and Welfare, 2002). Using the KCCR, we identified 3516 men who were diagnosed with gastric cancer from 1996 to 2002, from which we excluded the 64 people with multiple primary cancers.

We used anatomic site and histological classification information from the pathology reports of the KCCR based on the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology. Tumours at the oesophagogastric junction or upper third of the stomach were classified as cardia and upper-third gastric cancer (C16.0–16.1) and those at the lower end of the stomach as distal gastric cancer (C16.2–16.7). Mixed site (C16.8) and site not otherwise specified (C16.9) were regarded as unclassified. Virtually all (>98%) of the gastric cancers were confirmed histologically, 94% being adenocarcinoma (M814–857), and the few cases (n=212) that were not excluded. During the 6.5-year follow-up period, we included 3452 patients diagnosed with a gastric adenocarcinoma in a final cohort comprising 669 570 participants.

We also gathered 1996–2002 mortality data from the National Statistical Office. Subjects without cancer were followed until 31 December 2002; the follow-up period for each cancer case was defined as the interval between enrollment and diagnosis.

Statistical analysis

The Cox proportional hazard regression model was used to estimate the relative risk of gastric cancer by subsite according to smoking status and alcohol intake (first adjusted only for age, then adjusted for other potential risk factors). Every model included the length of follow-up as a time-dependent covariate. The proportionality assumption was verified by inspecting hazard plots. The trends were assessed by assigning ordinal values for categorical variables. Non- and former smokers were excluded from the analysis of duration and intensity (cigarettes per day) when calculating the P-value for trend, as suggested by Lefforondré et al (2002). For alcohol consumption, trends were calculated among those who drank at least 1 g per day.

The interaction effects were evaluated by calculating an interaction term, that is, multiplying a dummy variable for smoking (current smoker=1, nonsmoker or former smoker=0) by one for alcohol consumption (drinks once per month=1, never drinks=0). Interactions between smoking and alcohol drinking were formally tested using the likelihood ratio method, comparing models with and without the interaction terms. We calculated a population-attributable risk (Rothman and Greenland, 1998) to assess the potential public health impact of smoking on gastric cancer by anatomic site, using the smoking prevalence data from the 1998 Korea Health Survey (Ministry of Health and Welfare, 1999). All confidence intervals (CIs) were at 95%, and a P-value of 5% was considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS version 9.1 (SAS institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

The 669 570 study cohort members were followed for an average 6.5 years, contributing a total of 4 353 317 person-years. The population was primarily middle aged (mean of 44 years) and had a low average BMI (23.6 kg m−2) with 29.4% of men over 25 kg m−2. At baseline, 53.5 and 71.8% of the men were current smokers and drinkers, respectively (Table 1). During follow-up, we identified 3452 new cases of gastric cancer, of which 127 (4%) were cardia and upper-third cancers, 2409 (70%) were distal gastric cancer and 1007 were unclassified. Some characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1. Almost 90% of cases occurred in persons above 40 years.

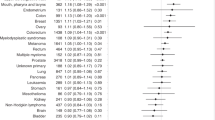

Table 2 shows the adjusted relative risk (aRR) for gastric cancer in relationship to smoking and alcohol intake. The risk of cardia and upper-third gastric cancers was doubled or more among current smokers (aRR=2.2; 95% CI=1.4–3.5) when compared to those who had never smoked. For distal and total gastric cancer, the corresponding risks of current and never smokers were 1.4 (95% CI=1.3–1.6) and 1.5 (95% CI=1.4–1.6), respectively. Relative risks of gastric cancer increased with increasing numbers of cigarettes per day and years of smoking, although the trend was not statistically significant. The age-only adjusted risk estimates for smoking changed only slightly after adjusting for alcohol and other variables (see Materials and Methods), including alcohol intake (data not shown). We estimated the multivariate-adjusted population-attributable risks from cigarette smoking as 36.8% (95% CI 16.2–52.4) in cardia and upper-third gastric cancer, and 19.3% (95% CI 13.9–24.3) in distal gastric cancer; overall, 22.5% (95% CI 18.3–26.5) of gastric cancers were attributable to smoking.

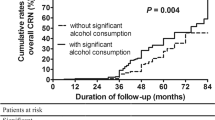

Alcohol consumption was also associated with an increased risk after adjusting for smoking status (Table 3). The risks of distal and total gastric cancers were increased among patients who reported drinking at least 25 g of alcohol per day to 1.3 (95% CI 1.2–1.5) and 1.2 (95% CI 1.1–1.4), respectively, when compared to nondrinkers, and the P-value for trend was significant when only drinkers were considered. Although the risks of cardia and upper-third gastric cancer were increased among drinkers, these were not significant.

The independent and joint effects of smoking and alcohol intake on risks by gastric subsite are examined in Table 4. Smoking over 20 cigarettes per day combined with alcohol consumption exceeding 25 g per day was associated with a nearly five-fold increased risk of cardia and upper-third gastric cancer (HR=4.5, 95% CI =1.7–11.9), and a two-fold increased risk of distal gastric cancer compared to nonusers. The interaction between smoking and alcohol drinking was not statistically significant for total gastric cancer (P=0.48), cardia and upper-third cancer (P=0.68) or distal cancer (P=0.89).

Discussion

Smoking and alcohol use were associated with gastric cancer risk by anatomic subsite in this large cohort study. Current smokers showed elevated risks, higher in cardia and upper-third than in distal gastric cancer among current smokers. Furthermore, we found that the risk of cancer increased with the number of cigarettes smoked per day and years of smoking. Positive associations were also found with alcohol consumption, though for cardia and upper-third gastric cancers this was not significant. The results of the multinomial logistic analysis were similar to those of a Cox proportional hazard regression: the incidence of cardia and upper-third gastric cancer was 2.2 times higher for current smokers than for never smokers, and 1.4 times for distal gastric cancer (data not shown). Combined exposure to high levels of tobacco and alcohol further increased the risk estimates.

Although smoking is well recognised as a moderate risk factor, few population-based cohort studies have been conducted for gastric subsites (Sasazuki et al, 2002; Koizumi et al, 2004; Sjödahl et al, 2006). In the last 5 years, seven case–control studies have also been reported: five of them (Gammon et al, 1997; Zaridze et al, 2002) observed a higher risk for cardia cancers, while two did not (Brenner et al, 2002). We found moderately strong associations between smoking and gastric cancer in both cardia and upper third, and distal locations. Several dose–response associations were also suggested, adding to evidence of a causal association.

Although a significant association of cardia cancer with alcohol has been reported (Inoue et al, 1994), most studies have not confirmed this (Okabayashi et al, 2000; Sasazuki et al, 2002; Zaridze et al, 2002). We found that alcohol intake was significantly related to an increased risk both of gastric cancer as a whole and of the distal stomach. By contrast, the positive association for cardia and upper-third cancers was not significant, perhaps because of the relatively small numbers.

Several potential limitations of our study resulted from the use of data collected as part of an insurance plan. First, the self-reported smoking and alcohol details were not validated, and the amount smoked per day was classified only as ‘1–9’ and ‘20 or more’ on the 1996 questionnaire. Therefore, we could not examine, for example, 15–24 cigarettes smoked daily to cover the effect of rounding to a common value.

Second, our study cohort was not representative of all Koreans. Although enrollment in the NHI Program is largely mandatory for Koreans, our study covered only employed persons (government employees and teachers) and their families, and consequently, may have under-represented heavy users of alcohol and tobacco. However, follow-up should be essentially complete because of our using record linkage with unique personal identifiers to national databases.

Third, we lacked information on Helicobacter pylori, a strong risk factor for gastric cancer (International Agency for Research on Cancer, 1994). In Korea, the reported prevalence of H. pylori IgG antibody among males above 40 years is 77–83% (Shin et al, 2005a; Kim et al, 2006). Moreover, a nonsignificant increased risk for gastric cancer associated with the presence of H. pylori was observed among subjects in a longer than 5-year follow-up study in Korea (Shin et al, 2005a). In addition, evidence has shown that the association of smoking and gastric cancer is independent of H. pylori infection (Siman et al, 2001; Sasazuki et al, 2002). Given these findings, the lack of H. pylori data is unlikely to be an important issue for interpreting our findings.

Fourth, no detailed information on nutritional factors was available, including the intake of antioxidative vitamins, which might have a protective effect against gastric cancer (Kono and Hirohata, 1996).

In our study, cardia and upper-third gastric cancer was more strongly related to smoking status than distal gastric cancer, while alcohol consumption may be associated with an increased risk of distal and total gastric cancer. Larger numbers of cardia gastric cancer, however, would be needed to investigate a dose–response relationship reliably.

Change history

16 November 2011

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Brenner H, Arndt V, Bode G, Stegmaier C, Ziegler H, Stumer T (2002) Risk of gastric cancer among smokers infected with Helicobacter pylori. Int J Cancer 98: 446–449

Gammon MD, Schoenberg JB, Ahsan H, Risch HA, Vaughan TL, Chow WH, Rotterdam H, West AB, Dubrow R, Stanford JL, Mayne ST, Farrow DC, Niwa S, Blot WJ, Fraumeni JF (1997) Tobacco, alcohol, and socioeconomic status and adenocarcinomas of the esophagus and gastric cardia. J Natl Cancer Inst 89: 1277–1284

Inoue M, Tajima K, Hirose K, Kuroishi T, Gao CM, Kitoh T (1994) Life-style and subsite of gastric cancer – joint effect of smoking and drinking habits. Int J Cancer 56: 494–499

International Agency for Research on Cancer (1994) IARC monograph on the evaluation of the carcinogenic risks to humans, Schistosomes, liver flukes and Helicobacter pylori, vol. 61. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer

International Agency for Research on Cancer (2004) Tobacco smoke and involuntary smoking. In IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risk to Humans, vol. 83, pp 557–613, Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer

Kim N, Lim SH, Lee KH, Kim JM, Gho SI, Jung HC, Song IS (2006) Seroconversion of Helicobacter in Korean male employees. Scand J Gastroenterol 40: 1021–1027

Koizumi Y, Tsubono Y, Nakaya N, Kuriyama S, Shibuya T, Matsuoka H, Tsuji I (2004) Cigarette smoking and the risk of gastric cancer: a pooled analysis of two prospective studies in Japan. Int J Cancer 112: 1049–1055

Kono S, Hirohata T (1996) Nutrition and stomach cancer. Cancer Causes Control 7: 41–55

Lefforondré K, Abrahamowicz M, Siemiatycki J, Rachet B (2002) Modeling smoking history: a comparison of different approaches. Am J Epidemiol 69: 239–241

Ministry of Health and Welfare (1999) 1998 Korea Health Survey – Summary Report. Seoul: Ministry of Health and Welfare

Ministry of Health and Welfare (2002) Korea: Annual Report of Korea Central Cancer Registry Program, January–December 2000 Seoul, Korea: Ministry of Health and Welfare

Okabayashi T, Gotoda T, Kondo H, Inui T, Ono H, Saito D, Yoshida S, Sasako M, Shimoda T (2000) Early carcinoma of the gastric cardia in Japan: is it different from that in the West? Cancer 89: 2555–2559

Park SM, Lim MK, Shin SA, Yun YH (2006) Impact of prediagnosis smoking, alcohol, obesity, and insulin resistance on survival in male cancer patients: National Health Insurance Corporation study. J Clin Oncol 24: 5017–5024

Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay T, Pisani P (2005) Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin 55: 74–108

Rothman KJ, Greenland S (1998) Modern Epidemiology, 2nd edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott–Raven Publishers

Sasazuki S, Sasaki S, Tsugane S (2002) Japan Public Health Center Study Group. Cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption and subsequent gastric cancer risk by subsite and histologic type. Int J Cancer 101: 560–566

Shin A, Shin HR, Kang D, Park SK, Kim CS, Yoo KY (2005a) A nested case–control study of the association of Helicobacter pylori infection with gastric adenocarcinoma in Korea. Br J Cancer 92: 1273–1275

Shin HR, Won YJ, Jung KW, Kong HJ, Yim SH, Lee JK, Noh HI, Lee JK, Pisani P, Park JG (2005b) Nationwide cancer incidence in Korea, 1999–2001: first result using the national cancer incidence database. Cancer Res Treat 37: 325–331

Siman JH, Forsgren A, Berglund G, Floren CH (2001) Tobacco smoking increases the risk for gastric adenocarcinoma among Helicobacter pylori-infected individuals. Scand J Gastroenterol 36: 208–213

Sjödahl K, Lu Y, Nilsen T, Ye W, Hveem K, Vatten L, Lagergren J (2006) Smoking and alcohol drinking in relation to risk of gastric cancer: a population-based prospective cohort study. Int J Cancer 120: 128–132

Tsugane S, Sasazuki S, Kobayashi M, Sasaki S (2004) Salt and salted food intake and subsequent risk of gastric cancer among middle-aged Japanese men and women. Br J Cancer 90 (1): 128–134

World Health Organisation (2000) International Association for the Study of Obesity, International Obesity Task Force. The Asia–Pacific perspective: reducing obesity and its treatment. Sydney: Health Communications Australia

Yun YH, Lim MK, Jung KW, Bae JM, Park SM, Shin SA, Lee JS, Park JG (2005) Relative and absolute risks of cigarette smoking on major histologic types of lung cancer in Korean men. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 14: 2125–2130

Zaridze D, Borisova E, Maximovitch D, Chkhikvadze V (2002) Alcohol consumption, smoking and risk of gastric cancer: case–control study from Moscow, Russia. Cancer Causes Control 11: 363–367

Acknowledgements

We thank the Korean Central Cancer Registry (KCCR) and the National Health Insurance Corporation for providing help. This work was supported by National Cancer Center grant 0710131-1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Sung, N., Choi, K., Park, E. et al. Smoking, alcohol and gastric cancer risk in Korean men: the National Health Insurance Corporation Study. Br J Cancer 97, 700–704 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6603893

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6603893

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Panel of significant risk factors predicts early stage gastric cancer and indication of poor prognostic association with pathogens and microsatellite stability

Genes and Environment (2021)

-

Clinicopathological Characteristics and Incidence of Gastric Cancer in Eastern India: A Retrospective Study

Journal of Gastrointestinal Cancer (2021)

-

Influence of metabolic syndrome on upper gastrointestinal disease

Clinical Journal of Gastroenterology (2016)

-

Interleukin-16 polymorphisms as new promising biomarkers for risk of gastric cancer

Tumor Biology (2016)

-

Cell-composition effects in the analysis of DNA methylation array data: a mathematical perspective

BMC Bioinformatics (2015)