Abstract

Purpose

It is unclear whether time between breast cancer diagnosis and surgery is associated with survival and whether this relationship is affected by access to care. We evaluated the association between time-to-surgery and overall survival among women in the universal-access U.S. Military Health System (MHS).

Methods

Women aged 18–79 who received surgical treatment for stages I–III breast cancer between 1998 and 2010 were identified in linked cancer registry and administrative databases with follow-up through 2015. Multivariable Cox regression models were used to estimate risk of all-cause death associated with time-to-surgery intervals.

Results

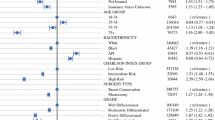

The study included 9669 women with 93.1% survival during the study period. The hazards ratios (95% confidence intervals) of all-cause death associated with time-to-surgery were 1.15 (0.93, 1.42) for 0 days, 1.00 (reference) for 1–21 days, 0.97 (0.78, 1.21) for 22–35 days, and 1.30 (1.04, 1.61) for ≥ 36 days. The higher risk of mortality associated with time-to-surgery ≥ 36 days tended to be consistent when analyzed by surgery type, age at diagnosis, and tumor stage.

Conclusions

In the MHS, longer time-to-surgery for breast cancer was associated with poorer overall survival, suggesting the importance of timeliness in receiving surgical treatment for breast cancer in relation to overall survival.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available due to the sensitive nature of the data and presence of protected health information (PHI). The Department of Defense Central Cancer Registry (CCR) data may be requested from the Joint Pathology Center; and the Military Health System Data Repository (MDR) data may be requested from the Defense Health Agency. Restrictions apply to the access and use of these data.

Abbreviations

- CCR:

-

Central Cancer Registry

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CPT:

-

Current Procedural Terminology

- ER:

-

Estrogen receptor

- FORDS:

-

Facility Oncology Registry Data Standards

- HCPCS:

-

Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System

- HR:

-

Hazards ratio

- ICD:

-

International Classification of Diseases

- MDR:

-

Military Health System Data Repository

- MHS:

-

Military Health System

- PR:

-

Progesterone receptor

- SEER:

-

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program

- TTS:

-

Time-to-surgery

References

Kaufman CS, Shockney L, Rabinowitz B et al (2010) National quality measures for breast centers (NQMBC): a robust quality tool: Breast center quality measures. Ann Surg Oncol 17(2):377–385

Del Turco MR, Ponti A, Bick U et al (2010) Quality indicators in breast cancer care. Eur J Cancer 46(13):2344–2356

Comber H, Cronin DP, Deady S et al (2005) Delays in treatment in the cancer services: impact on cancer stage and survival. Ir Med J 98(8):238–239

Brazda A, Estroff J, Euhus D et al (2010) Delays in time to treatment and survival impact in breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 17(Suppl 3):291–296

Neal RD, Tharmanathan P, France B et al (2015) Is increased time to diagnosis and treatment in symptomatic cancer associated with poorer outcomes? Systematic review. Br J Cancer 112(Suppl 1):S92–S107

Bleicher RJ, Ruth K, Sigurdson ER et al (2016) Time to surgery and breast cancer survival in the United States. JAMA Oncol 2(3):330–339

Smith EC, Ziogas A, Anton-Culver H (2013) Delay in surgical treatment and survival after breast cancer diagnosis in young women by race/ethnicity. JAMA Surg 148(6):516–523

Mariella M, Kimbrough CW, McMasters KM, Ajkay N (2018) Longer time intervals from diagnosis to surgical treatment in breast cancer: associated factors and survival impact. Am Surg 84(1):63–70

Gu J, Groot G, Boden C et al (2018) Review of factors influencing women’s choice of mastectomy versus breast conserving therapy in early stage breast cancer: a systematic review. Clin Breast Cancer 18(4):e539–e554

Lizarraga I, Schroeder MC, Weigel RJ, Thomas A (2015) Surgical management of breast cancer in 2010-2011 SEER registries by hormone and her2 receptor status. Ann Surg Oncol 22(Suppl 3):S566–S572

Nijenhuis MV, Rutgers EJ (2013) Who should not undergo breast conservation? Breast 22(Suppl 2):S110–S114

Bleicher RJ, Ruth K, Sigurdson ER et al (2012) Preoperative delays in the us medicare population with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 30(36):4485–4492

McGee SA, Durham DD, Tse CK, Millikan RC (2013) Determinants of breast cancer treatment delay differ for african american and white women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 22(7):1227–1238

Golshan M, Losk K, Kadish S et al (2014) Understanding process-of-care delays in surgical treatment of breast cancer at a comprehensive cancer center. Breast Cancer Res Treat 148(1):125–133

Freedman RA, Partridge AH (2013) Management of breast cancer in very young women. Breast 22(Suppl 2):S176–S179

Dietz JR, Partridge AH, Gemignani ML et al (2015) Breast cancer management updates: young and older, pregnant, or male. Ann Surg Oncol 22(10):3219–3224

Wang J, Kollias J, Boult M et al (2010) Patterns of surgical treatment for women with breast cancer in relation to age. Breast J 16(1):60–65

Yancik R, Wesley MN, Ries LA et al (2001) Effect of age and comorbidity in postmenopausal breast cancer patients aged 55 years and older. JAMA 285(7):885–892

Coughlin SS, Calle EE, Teras LR et al (2004) Diabetes mellitus as a predictor of cancer mortality in a large cohort of US adults. Am J Epidemiol 159(12):1160–1167

Calip GS, Malone KE, Gralow JR et al (2014) Metabolic syndrome and outcomes following early-stage breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 148(2):363–377

Walker GV, Grant SR, Guadagnolo BA et al (2014) Disparities in stage at diagnosis, treatment, and survival in nonelderly adult patients with cancer according to insurance status. J Clin Oncol 32(28):3118–3125

Abdelsattar ZM, Hendren S, Wong SL (2017) The impact of health insurance on cancer care in disadvantaged communities. Cancer 123(7):1219–1227

Zhang Y, Franzini L, Chan W et al (2015) Effects of health insurance on tumor stage, treatment, and survival in large cohorts of patients with breast and colorectal cancer. J Health Care Poor Underserved 26(4):1336–1358

Lee-Feldstein A, Feldstein PJ, Buchmueller T, Katterhagen G (2000) The relationship of HMOs, health insurance, and delivery systems to breast cancer outcomes. Med Care 38(7):705–718

Rosenberg AR, Kroon L, Chen L et al (2015) Insurance status and risk of cancer mortality among adolescents and young adults. Cancer 121(8):1279–1286

Hsu CD, Wang X, Habif DV Jr et al (2017) Breast cancer stage variation and survival in association with insurance status and sociodemographic factors in US women 18 to 64 years old. Cancer 123(16):3125–3131

Niu X, Roche LM, Pawlish KS, Henry KA (2013) Cancer survival disparities by health insurance status. Cancer Med 2(3):403–411

Mayberry RM, Mili F, Ofili E (2000) Racial and ethnic differences in access to medical care. Med Care Res Rev 57(Suppl 1):108–145

Barnett JC, Berchick ER (2017) Current population reports: Health insurance coverage in the United States, 2016, U.S. Census Bureau, Editor. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC

Akinyemiju TF, Soliman AS, Johnson NJ et al (2013) Individual and neighborhood socioeconomic status and healthcare resources in relation to black-white breast cancer survival disparities. J Cancer Epidemiol. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/490472

Wheeler SB, Reeder-Hayes KE, Carey LA (2013) Disparities in breast cancer treatment and outcomes: biological, social, and health system determinants and opportunities for research. Oncologist 18(9):986–993

Defense Health Agency Decision Support Division (2018) Evaluation of the TRICARE program: Fiscal year 2018 report to congress, Defense Health Agency and Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense (Health Affairs) (OASD[HA]), Editors. pp 1–206. http://health.mil

The Department of Defense Joint Pathology Center (2014) DoD Cancer Registry Program. 2014. https://www.jpc.capmed.mil

Defense Health Agency: Military health system data repository (2017) https://www.health.mil/Military-Health-Topics/Technology/Clinical-Support/Military-Health-System-Data-Repository

Commission on Cancer (2016) Facility oncology registry data standards. American College of Surgeons, Chicago, IL

Gradishar WJ, Anderson BO, Balassanian R et al (2018) Breast cancer, version 4.2017, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 16(3):310–320

American Joint Committee on Cancer (2002) American Joint Committee on Cancer: Part VII: Breast. In: Greene FL, Page DL, Fleming ID, Fritz AG et al (eds) AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. Springer, Chicago, IL, pp 223–240

Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG et al (eds) (2010) AJCC cancer staging manual, 7th edn. Springer, Chicago

Eaglehouse YL, Manjelievskaia J, Shao S et al (2018) Costs for breast cancer care in the military health system: an analysis by benefit type and care source. Mil Med 183(11–12):e500–e508

Slade C, Talbot R (2007) Sustainability of cancer waiting times: the need to focus on pathways relevant to the cancer type. J R Soc Med 100(7):309–313

Crawford SC, Davis JA, Siddiqui NA et al (2002) The waiting time paradox: population based retrospective study of treatment delay and survival of women with endometrial cancer in Scotland. BMJ 325(7357):196

Defense Health Agency (2019) Tricare. www.tricare.mil

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR (1987) A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 40(5):373–383

Mihalcik SA, Rawal B, Braunstein LZ et al (2017) The impact of reexcision and residual disease on local recurrence following breast-conserving therapy. Ann Surg Oncol 24(7):1868–1873

Fredriksson I, Liljegren G, Palm-Sjovall M et al (2003) Risk factors for local recurrence after breast-conserving surgery. Br J Surg 90(9):1093–1102

Bilimoria KY, Ko CY, Tomlinson JS et al (2011) Wait times for cancer surgery in the United States: trends and predictors of delays. Ann Surg 253(4):779–785

Murphy AE, Hussain L, Ho C et al (2017) Preoperative panel testing for hereditary cancer syndromes does not significantly impact time to surgery for newly diagnosed breast cancer patients compared with brca1/2 testing. Ann Surg Oncol 24(10):3055–3059

National Cancer Institute (2018) Her2’s genetic link to breast cancer spurs development of new treatments. Stories of Discovery. https://www.cancer.gov/research/progress/discovery/her2

Haslam A, Prasad V (2019) Estimation of the percentage of us patients with cancer who are eligible for and respond to checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy drugs. JAMA Netw Open 2(5):e192535–e192535

Goddard KAB, Weinmann S, Richert-Boe K et al (2011) Her2 evaluation and its impact on breast cancer treatment decisions. Public Health Genomics 15(1):1–10

Krishnamurti U, Silverman JF (2014) Her2 in breast cancer: a review and update. Adv Anat Pathol 21(2):100–107

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Joint Pathology Center and Defense Health Agency for providing the data used in this study.

Disclaimer

The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not reflect the views, assertions, opinions or policies of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USUHS), the Department of Defense (DoD), or the Departments of the Army, Navy, or Air Force, or any other agency of the U.S. Government, or the Henry M. Jackson Foundation (HJF). Mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Funding

This project was supported by the Murtha Cancer Center Research Program, Department of Surgery, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences and Walter Reed National Military Medical Center under the auspices of the Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The data linkage project was reviewed and approved by the institutional review boards of the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center and the Defense Health Agency for compliance with ethical standards. All study activities were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional review boards and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. It was determined by the institutional review boards that formal consent was not required for this type of study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Eaglehouse, Y.L., Georg, M.W., Shriver, C.D. et al. Time-to-surgery and overall survival after breast cancer diagnosis in a universal health system. Breast Cancer Res Treat 178, 441–450 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-019-05404-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-019-05404-8