Abstract

Summary

Weekly bisphosphonates are the primary agents used to treat osteoporosis. Although these agents are generally well tolerated, serious gastrointestinal adverse events, including hospitalization for gastrointestinal bleed, may arise. We compared the gastrointestinal safety between weekly alendronate and weekly risedronate and found no important difference between new users of these agents.

Introduction

Weekly bisphosphonates are the primary agents prescribed for osteoporosis. We examined the comparative gastrointestinal safety between weekly bisphosphonates.

Methods

We studied new users of weekly alendronate and weekly risedronate from June 2002 to August 2005 among enrollees in a state-wide pharmaceutical benefit program for seniors. Our primary outcome was hospitalization for upper gastrointestinal bleed. Secondary outcomes included outpatient diagnoses for upper gastrointestinal disease, symptoms, endoscopic procedures, use of gastroprotective agents, and switching between therapies. We used Cox proportional hazard models to compare outcomes between agents within 120 days of treatment initiation, adjusting for propensity score quintiles. We also examined composite safety outcomes and stratified results by age and prior gastrointestinal history.

Results

A total of 10,420 new users were studied, mean age = 79 years (SD, 6.9), and 95% women. We observed 31 hospitalizations for upper gastrointestinal bleed (0.91 per 100 person-years) within 120 days of treatment initiation. Adjusting for covariates, there was no difference in hospitalization for upper gastrointestinal bleed among those treated with risedronate compared with alendronate (HR, 1.12; 95%CI, 0.55 to 2.28). Risedronate switching rates were lower; otherwise, no differences were observed for secondary or composite outcomes.

Conclusions

We found no important difference in gastrointestinal safety between weekly oral bisphosphonates.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Stafford RS, Drieling RL, Hersh AL (2004) National trends in osteoporosis visits and osteoporosis treatment, 1988–2003. Arch Intern Med 164:1525–1530

Lee E, Wutoh AK, Xue Z, Hillman JJ, Zuckerman IH (2006) Osteoporosis management in a Medicaid population after the Women’s Health Initiative study. J Womens Health 15:155–161

Udell JA, Fischer MA, Brookhart MA, Solomon DH, Choudhry NK (2006) Effect of the Women’s Health Initiative on osteoporosis therapy and expenditure in Medicaid. J Bone Miner Res 21:765–771

Cadarette SM, Katz JN, Brookhart MA, Levin R, Stedman MR, Choudhry NK, Solomon DH (2008) Trends in drug prescribing for osteoporosis after hip fracture, 1995–2004. J Rheumatol 35:319–326

Bobba RS, Beattie K, Parkinson B, Kumbhare D, Adachi JD (2006) Tolerability of different dosing regimens of bisphosphonates for the treatment of osteoporosis and malignant bone disease. Drug Safety 29:1133–1152

Lanza FL, Hunt RH, Thomson ABR, Provenza JM, Blank MA, Risedronate Endoscopy Study Group (2000) Endoscopic comparison of esophageal and gastroduodenal effects of risedronate and alendronate in postmenopausal women. Gastroenterol 119:631–638

Thomson ABR, Marshall JK, Hunt RH, Provenza JM, Lanza FL, Royer MG, Li Z, Blank MA, Risedronate Endoscopy Study Group (2002) 14 day endoscopy study comparing risedronate and alendronate in postmenopausal women stratified by Helicobacter pylori status. J Rheumatol 29:1965–1974

Kane S, Borisov NN, Brixner D (2004) Pharmacoeconomic evaluation of gastrointestinal tract events during treatment with risedronate or alendronate: a retrospective cohort study. Am J Manag Care 10:S216–S226

Miller RG, Bologness M, Worley K, Solis A, Sheer R (2004) Incidence of gastrointestinal events among bisphosphonate patients in an observational setting. Am J Manag Care 10:S207–S215

Rosen CJ, Hochberg MC, Bonnick SL, McClung M, Miller P, Broy S, Kagan R, Chen E, Petruschke RA, Thompson DE, de Papp AE, Fosamax Actonel Comparison Trial Investigators (2005) Treatment with once-weekly alendronate 70 mg compared with once-weekly risedronate 35 mg in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis: a randomized double-blind study. J Bone Miner Res 20:141–151

Bonnick S, Saag KG, Kiel DP, McClung M, Hochberg M, Burnett SM, Sebba A, Kagan R, Chen E, Thompson DE, de Papp AE, Fosamax Actonel Comparison Trial (FACT) Investigators (2006) Comparison of weekly treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis with alendronate versus risedronate over two years. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91:2631–2637

Epstein S, Delmas PD, Emkey R, Wilson KM, Hiltbrunner V, Schimmer RC (2006) Oral ibandronate in the management of postmenopausal osteoporosis: review of upper gastrointestinal safety. Maturitas 54:1–10

Schneeweiss S, Avorn J (2005) A review of uses of health care utilization databases for epidemiologic research on therapeutics. J Clin Epidemiol 58:323–337

Rainford DS, Gutthann SP, Rodriguez LAG (1996) Positive predictive value of ICD-9 codes in the identification of cases of complicated peptic ulcer disease in the Saskatchewan Hospital Automated Database. Epidemiol 7:101–104

Cattaruzzi C, Troncon MG, Agostinis L, Rodriguez LAG (1999) Positive predictive value of ICD-9th codes for upper gastrointestinal bleeding and perforation in the Sistema Informativo Sanitario Regionale Database. J Clin Epidemiol 52:499–502

Dalton SO, Johansen C, Mellemkjær L, Nørgård B, Sørensen HT, Olsen JH (2003) Use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and risk of upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding: a population-based cohort study. Arch Intern Med 163:59–64

Donahue JG, Chan KA, Andrade SE, Beck A, Boles M, Buist DSM, Carey VJ, Chandler JM, Chase GA, Ettinger B, Fishman P, Goodman M, Guess HA, Gurwitz JH, LaCroix AZ, Levin TR, Platt R (2002) Gastric and duodenal safety of daily alendronate. Arch Intern Med 162:936–942

Jacobson BC, Somers SC, Fuchs CS, Kelly CP, Camargo CA (2006) Body-mass index and symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux in women. New Engl J Med 354:2340–2348

Zullo A, Hassan C, Campo SMA, Morini S (2007) Bleeding peptic ulcer in the elderly: risk factors and prevention strategies. Drugs Aging 24:815–828

Tata LJ, Fortun PJ, Hubbard RB, Smeeth L, Hawkey CJ, Smith CJP, Whitaker HJ, Farrington CP, Card TR, West J (2005) Does concurrent prescription of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs substantially increase the risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding? Aliment Pharmacol Ther 22:175–181

Hernández-Diaz S, Rodriguez LAG (2000) Association between nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding/perforation: an overview of epidemiologic studies published in the 1990 s. Arch Intern Med 160:2093–2099

Yamaguchi T, Sugimoto T, Yamauchi M, Matsumori Y, Tsutsumi M, Chihara K (2005) Multiple vertebral fractures are associated with refractory reflux esophagitis in postmenopausal women. J Bone Miner Metab 23:36–40

Weil J, Langman MJS, Wainwright P, Lawson DH, Rawlins M, Logan RFA, Brown TP, Vessey MP, Murphy M, Colin-Jones DG (2000) Peptic ulcer bleeding: accessory risk factors and interactions with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Gut 46:27–31

Ramakrishnan K, Salinas RC (2007) Peptic ulcer disease. Am Fam Physician 76:1005–1012

Udd M, Miettinen P, Palmu A, Heikkinen M, Janathuinen E, Pasanen P, Tarvainen R, Mustonen H, Julkunen R (2007) Analysis of the risk factors and their combinations in acute gastroduodenal ulcer bleeding: a case-control study. Scand J Gastroenterol 42:1395–1403

Stürmer T, Schneeweiss S, Brookhart MA, Rothman KJ, Avorn J, Glynn RJ (2005) Analytic strategies to adjust confounding using exposure propensity scores and disease risk scores: nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and short-term mortality in the elderly. Am J Epidemiol 161:891–898

Stürmer T, Joshi M, Glynn RJ, Avorn J, Rothman KJ, Schneeweiss S (2006) A review of the application of propensity score methods yielded increasing use, advantages in specific settings, but not substantially different estimates compared with conventional multivariable methods. J Clin Epidemiol 59:437–447

Glynn RJ, Schneeweiss S, Stürmer T (2006) Indications for propensity scores and review of their use in pharmacoepidemiology. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 98:253–259

Schneeweiss S (2006) Sensitivity analysis and external adjustment for unmeasured confounders in epidemiologic database studies of therapeutics. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 15:291–303

MacLean C, Newberry S, Maglione M, McMahon M, Ranganath V, Suttorp M, Mojica W, Timmer M, Alexander A, McNamara M, Desai SB, Zhou A, Chen S, Carter J, Tringale C, Valentine D, Johnsen B, Grossman J (2008) Systematic review: comparative effectiveness of treatments to prevent fractures in men and women with low bone density or osteoporosis. Ann Intern Med 148:197–213

Lindsay R (2007) Beyond clinical trials: the importance of large databases in evaluating differences in the effectiveness of bisphosphonate therapy in postmenopausal osteoporosis. Bone 40:S32–S35

Curtis JR, Westfall AO, Allison JJ, Freeman A, Saag KG (2006) Channeling and adherence with alendronate and risedronate among chronic glucocorticoid users. Osteoporos Int 17:1268–1274

Tosteson ANA, Grove MR, Hammond CS, Moncur MM, Ray GT, Hebert GM, Pressman AR, Ettinger B (2003) Early discontinuation of treatment for osteoporosis. Am J Med 115:209–216

Carr AJ, Thompson PW, Cooper C (2006) Factors associated with adherence and persistence to bisphosphonate therapy in osteoporosis: a cross-sectional survey. Osteoporos Int 17:1638–1644

Ideguchi H, Ohno S, Hattori H, Ishigatsubo Y (2007) Persistence with bisphophonate therapy including treatment courses with multiple sequential bisphosphonates in the real world. Osteoporos Int 18:1421–1427

Hamilton B, McCoy K, Taggart H (2003) Tolerability and compliance with risedronate in clinical practice. Osteoporos Int 14:259–262

Moride Y, Abenhaim L (1994) Evidence of the depletion of susceptibles effect in non-experimental pharmacoepidemiologic research. J Clin Epidemiol 47:731–737

Cooper GS, Chak A, Lloyd LE, Yurchick PJ, Harper DL, Rosenthal GE (2000) The accuracy of diagnosis and procedural codes for patients with upper GI hemorrhage. Gastrointest Endosc 51:423–426

Schneeweiss S, Wang PS, Avorn J, Maclure M, Levin R, Glynn RJ (2004) Consistency of performance ranking of comorbidity adjustment scores in Canadian and U.S. utilization data. J Gen Intern Med 19:444–450

Romano PS, Roos LL, Jollis JG (1993) Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative data: differing perspectives. J Clin Epidemiol 46:1075–1079

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Sebastian Schneeweiss, MD, ScD, Director for Drug Evaluation and Outcomes Research, Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, for helpful comments and discussions.

Grant support

Dr Brookhart is supported by the National Institute on Aging (K25 AG027400), Dr Cadarette was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Post-Doctoral Fellowship), Dr Katz is supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Muskuloskeletal and Skin Diseases (K24 AR02123 and P60 AR47782), Dr Solomon is supported by the Arthritis Foundation and the National Institutes of Health (K24 AR055989, R21 AG027066, and P60 AR47782), and Dr. Stürmer is supported by the National Institute on Aging (RO1 AG023178) and the UNC-GSK Center for Excellence in Pharmacoepidemiology and Public Health.

Conflicts of interest

Co-authors have received salary support in the last 5 years from research grants to the Brigham and Women’s Hospital for unrelated work from: Amgen (Dr Brookhart), GlaxoSmithKline (Dr Stürmer), Merck (Drs. Solomon and Stürmer), Novartis (Dr Katz), Pfizer, Procter & Gamble, and Savient (Dr Solomon). There was no pharmaceutical industry support for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

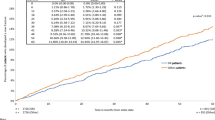

Sensitivity analysis of residual confounding using the array approach for our primary outcome (hospitalization for upper gastrointestinal bleed). To facilitate interpretation by the reader, we have maintained the notation used in the explanatory article and Excel program that we modified (available at www.drugepi.org) to produce this figure [29]. ARR apparent exposure relative risk, i.e., the relative risk (hazard ratio) observed in the current study (risedronate versus alendronate), fixed at 1.12. P C0 prevalence of counfounder among unexposed (alendronate), fixed at 20% in this example. P C1 prevalence of confounder among exposed (risedronate) group, varied from 0% to 50% in the figure. RR CD association between confounder and disease outcome, varied from 1.0 to 5.5 in figure. RR fully adjusted or “true” exposure relative risk. Blue line no confounding present, prevalence of confounder same among alendronate and risedronate recipients

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cadarette, S.M., Katz, J.N., Brookhart, M.A. et al. Comparative gastrointestinal safety of weekly oral bisphosphonates. Osteoporos Int 20, 1735–1747 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-009-0871-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-009-0871-8